Mark Dion and Alexandra Golaszewska

A WheatonArts Interview

How did you get involved with Emanation: Art + Process?

MD: Well, Hank Adams and Kristin Qualls from WheatonArts invited me down for a visit to discuss the exhibition. I had heard about WheatonArts for a long time since my friend, the artist Bryan Wilson, had worked there and spoke very highly of the place. Rather than go alone, I brought my fourteen Columbia University Fine Arts Graduate students with me. So I first encountered the production facilities, museum and grounds through their eyes. I saw how amazing they thought the place was and how relevant to the issues of production are to what they are engaged with as makers. We were hosted by Hank who conducted an introduction to sand casting for my group. The students could not have been more turned on and enthusiastic, which really surprised me.

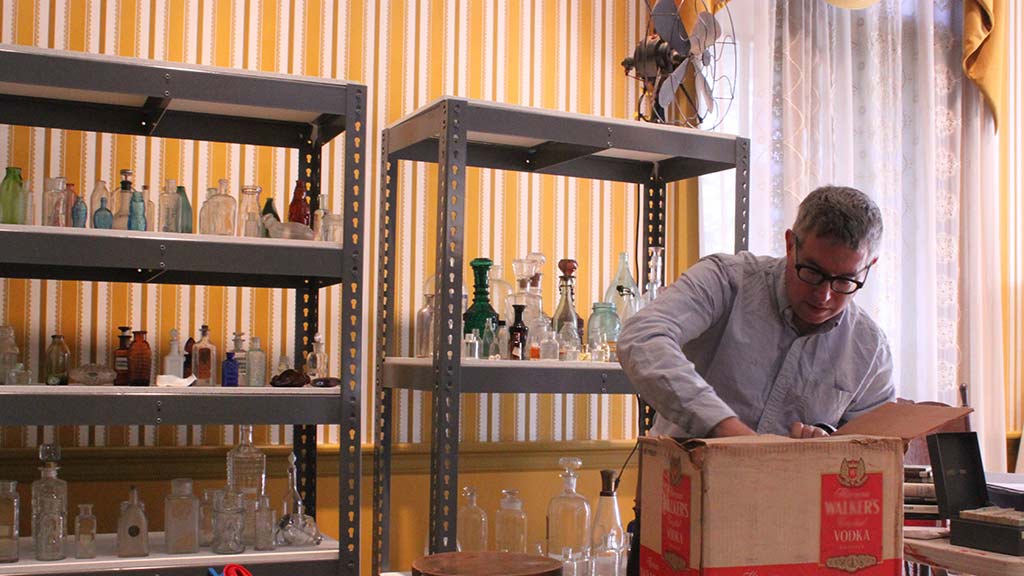

Kristin gave us a brilliant tour of the museum which was amazing and very open and of good humor. I am passionately invested in museums and the politics of display. For me it was clear that the entire social history of the site and collection was rich for investigation. Best of all, I was ushered behind the scenes to see of the oddball material which exists but is not accessioned into the collection and can be used as art material. This is an absurdly heterogeneous gathering of things like top hats, adding machines, ancient advertisement, quack medicines, and thousands of old bottles.

What were your expectations about WheatonArts? How did they match up with your experience when you arrived?

MD: First of all, everything I had ever heard about Wheaton made me think it was an actual planned industrial community, like those of Ford, Pullman or Edison. We arrived in the dark, so the illusion of that remained in tact. It was not until the morning that I was able to look with care at the village and discern the artifice of the place. Rather than the remnants of a model factory village, I discovered a simulacrum, a copy of a copy of an ideal. Much of my work deals with artifice, truthiness, and questions of how we know what we know, mediated by institutions like museums. Therefore Wheaton seemed a place with great potential for my kind of intervention.

How did you get interested in working with glass?

MD: Glass is a rich territory because it has such a strong place in both the everyday and domain of high art. Many of my friends and former assistants have come through the art glass world. Through Rachel Berwick at RISD and Josiah McElheny I have been introduced to a broad and complex cosmos of artists working with and about glass. Of course for me glass is an essential element in my interest in contextual investigations of art, the history of science and museum culture. So much of the culture of nature is behind glass. Just think of how many life forms have been displayed under bell jars, through lenses, behind vitrines, in Petri dishes. Glass is an essential foundation for presenting and understanding the natural world. Just imagine how many square feet of plate glass exist in the American Museum of Natural History. Of course the convention of using glass for display is employed in most other types of museums a well, from Zoos to Social History and Art Museums.

What has been inspiring to you from the museum exhibits and displays?

MD: WheatonArts Museum is an amazing institution. It presents the history of glass, but not in a linear and exhaustive manner. The history of glass if totally fascinating but often difficult to convey in a compelling way. What makes the history so interesting is that there are physical, material artifacts from the entire story. The tale of the evolution of the technology, the style shifts, innovations, and uses are imminent in the objects themselves. Glass is also a material which has a fundamental popular narrative. Glass has been a part of everyday life for so long and in so many ways that it is easy to develop a project touching a variety of topics, from marketing, industrial design and global commerce to display, collecting culture, laboratory science, photography and tourism. The museum is an excellent example of how to take a social history approach to such a complex material-based exhibition program.

What are you working on in your studio right now?

MD: My schedule at the moment is absurdly full. However each of the projects I am developing for the time around Emanation: Art + Process articulates aspects of the culture of collecting. “The Wonder Workshop” is a project with the V-A-C Foundation in Venice which explores the objects and ideas around the Wunderkammen of the 16th and 17th century. This work attempts to interrogate the origins of collections from the European tradition. At The Barnes Foundation, I am working on a project called “The Incomplete Naturalist”, which looks at the destructive character of collection as an activity. The work asks the question, what if Dr. Barnes has been a naturalist collector rather than an art collector? These projects all open within days of Emanation: Art + Process.

Can you describe your working routine?

MD: Being an artist for me means not having a routine. That is entirely the point of being an artist. It is fundamentally a lifestyle choice.

Can you describe your studio space and how, if at all, that affects your work?

MD: I am not and have never really been much of a studio based artist. Yes, my work has a strong material core, but it does not come from me working in one place, hammering out ideas in material form and experimenting with techniques. I often work with a team of highly skilled makers. When we need a studio we rent on short term, take all of our tools out of storage and produce like crazy. When we made what we need to, we disperse the team, close the studio and put the tools back into storage. While I do have the main studio in Pennsylvania, we use that more for art and material storage, building crates and framing. Only rarely do I make sculptures there.

Tell me about your process, where things begin, how they evolve etc.

MD: The site is where everything starts. My work is the result of a response to place and context. I have a very hard time making things for white walls. My process is one of listening to the site, exploring its social history and tying to find The Thread. Of course I do not arrive at the site empty-handed, I have my conceptual tool bag of concerns, themes and methods. The site is quite an expanded field. It is not merely the location in space, but also the history of the place, it’s specific architecture, but also the resources provided by the place, staff, abilities and expertise, and funds. Part of the site is also temporal: what is going on at the time, what is the zeitgeist.

Do you experiment with different materials a lot or do you prefer to work within certain parameters?

MD: My main talent as an artist has been the ability to read a site quickly and respond to the context. I know with great precision what I want the work to look like. When I have time, I make a drawing to represent the work and that helps translate the labor required to my team and helpers. I only experiment in the final process of installation, but even then it is a matter of detail and not significant substance.

As you look back through art history, whose work has been influential to you?

MD: To trace back an art historical lineage, is complicated but not terribly hard. It would go from ecological systems artists like Hans Haacke and Mel Chin, through Robert Smithson and the Earth Art and archaeological urbanists like Gordon Matta-Clark, past regional landscape traditions of O’Keeffe, Avery and Benton. An important marker would be the Hudson River School painters of the 19th Century, and Caleb Bingham. Then the naturalists artists working in early America, like Audubon, Wilson, Casby; as well as colonial naturalist artists worldwide. The Surrealists’ exploration of the uncanny aspects of nature and Henri Rousseau. The Barbizon School, the French animal sculptures, European romantic landscape painters, Delacroix, and of course Poussin and Claude Lorrain.

I owe a debt to northern Baroque Dutch and Flemish artists, particularly Jan Brueghel, Frans Syders, and David Teniers. Golden Age still life painting is something look at all the time. The Wunderkammer tradition and the Renaissance masters, Durer, Brueghel and Leonardo da Vinci contribute to my understanding of the social space that is Nature. Indian miniature painting of animal and landscape topics, as well animal sculpture from diverse cultures around the world has shaped my vision. The numerous classical depictions of mythic and real animals in mosaic, paint, ceramic, and marble are part of the lineage. We end of course at cave painting, the first known visual expressions, which produced a significant collection of animal depictions. So if your field of concern is the culture of nature, it can easily be perceived as an unbroken chain threading through numerous societies and cultures back to the first appearance of culture itself.

Can you tell us a little about your early years and what influenced you to become an artist?

MD: I grew up the great commonwealth of Massachusetts. There is a lot of New England in me and a lot of me in New England. My family was loving and supportive but not engaged in education. I can not recall my mother or father ever critically making an observation about culture of any kind. During my lifetime they never read a book and almost never visited a museum. I visited the New Bedford Whaling Museum as a boy during a field trip. It was a significant occasion. I really specifically recall encountering my first painting: the spectacular “Whaling Ships Trapped in Ice” by William Bradford. From the start I was captured by museum culture, by a place where one obtained knowledge through an encounter with material objects.

At high school I studied art in a very small class under the bell tower of Fairhaven High. I sat next to a lovely intelligent girl and was instructed by a lazy chain smoker who mostly just left us alone so he could smoke in his office. We listened to the radio, chatted, made drawings and enjoyed a sense of freedom not usually experienced by high school students. This was my first indication that being an artist meant having a degree of autonomy and personal responsibility, very different from having a job. If being an artist meant working on your production, spending the time as wished, listening to music and freely conversing and not being policed, then count me in.

What have been some of your most important influences that shaped how you create today?

MD: My work today remains committed to an exploration of the history of ideas which develop and mould the cultures of nature, which shape the landscape around us. This topic unavoidably leads to some pretty dark and depressing places since the terrible environmental news around the world so drastically outnumbers the positive news. Another tract of course in my work is looking at institutions mandated to educate and elucidate the social world around us. These museums which continue to evolve new and sophisticated strategies all the time, influence my own work. Museum exhibition designers look to visual artist for ideas, and we look to them as well. As a group of professionals, we have often read the same books, visited the same places and have some of the same goals. However we do not share the same responsibilities and we may diverge in strategies and tactics. Never the less, I look to museums for inspiration and material all the time.

Alexandra Golaszewska and Mark Dion – March 2015

Mark Dion is represented by Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, NYC, NY. In the Philadelphia region he is currently showing at The Barnes Foundation with fellow Emanation artist Judith Pfaff.